Ararat is marked by a an inconspicuous sign standing lonely by the side of East River Road on the west side of Grand Island, New York. Between a new apartment complex, a wildlife management area, and a cemetery, down the road from a marina and Radisson Hotel, stands the marker for an imagined American homeland for the world’s Jewry, and a testament to one of the stranger figures in Jewish American history.

Mordecai Manuel Noah was a famed writer and politician of the early 19th century. Born in the United States of Sephardic descent, he was probably the best-known Jew in the country. During his life, he would come to wield great influence and wealth as a New York politician and a part of the Tammany Hall Political Machine. His legacy lies interestingly at the intersections of race in early America and Jewish utopianism. Noah is one of the more complicated figures in Jewish American history, as he represents just how much the standing of Jews in the United States has changed over the decades and centuries. In Jewish Agricultural Utopias in America, his projects and motivations are relegated to a short blurb introducing the topic rather than expanding it.

Ararat, New York, intended by Noah to be a Jewish city of refuge tucked beside Niagara Falls on Grand Island, was never truly realized. Ararat was named after the Hebrew name for the Armenian highlands, a name which is still carried today by Mount Ararat, in Eastern Turkey. Knowing this, one cannot help but compare and contrast the two location of Niagara Falls and the Southern Caucasus. Most importantly, however, Ararat is known as the place where Noah’s Ark ran aground, a reference perhaps to both Mordecai Manuel Noah’s surname and to the location of Grand Island in the Niagara River (or maybe an allusion to the movement of people across the Atlantic). Either way, I would consider the vision of Ararat an apocalyptic landscape, even if just for its namesake.

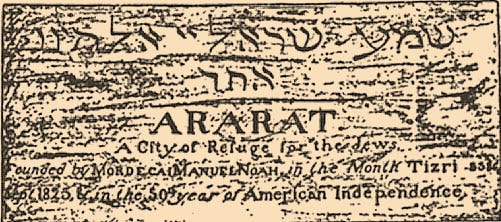

Though Noah purchased a large part of the island and dedicated a stone (which now is in the possession of the Buffalo History Museum) to the foundation of the city, it never appeared. Part of what I find fascinating about the Ararat Stone, which originally marked the dedication of the city, is that it situates itself chronologically in relation to two things: the Torah and American Independence. The dedication on the stone itself lies inscribed beneath the Sh’ma, the most important prayer of Judaism, which calls upon the people of Israel to acknowledge the oneness of God over them. It reads first the Hebrew date on which Ararat was founded by Mordecai Manuel Noah — the month of Tizri in the year 5586 — and then it does something interesting, and effectively establishes and American calendar in parity with the Hebrew one, reading “in the 50th year of American Independence” (which would make America’s independence 1775, not 1776). One thing to contemplate here as well is the comparative weights of these two dates. The American date tracks back to independence, while the Hebrew date tracks back to the creation of the universe as stated in the Torah. To position these two calendars right beside each other lends insight into the importance of American Independence to Noah, who was a lifelong politician, and his proto-Zionist conception of Jewish statehood.

This is how I largely view the legacy of Noah — it remained as a ghost hanging over subsequent movements and events in Jewish American history, but if someone were to claim that his actions directly, materially changed the trajectory of Jewish American history, I might disagree. I view him (and I am open to correction) as very much a prelude to what would happen closer to the turn of the century with the pogroms of the Russian Empire in the early 1880s.

I will also add that a large part of Noah’s legacy, of his own accord, was his racism. Mordecai Manuel Noah believed, as did Joseph Smith, that Indigenous Americans were not descended from their own heritage, but rather from the lost tribes of Israel. It seems this was actually quite a pervasive idea at the time amongst non-Indigenous Americans, but it does frame both of their projects in a different light when one considers that they viewed the American continent to be natively inhabited by Hebrews. Perhaps this is what made the location of Grand Island, traditionally land of the Neutral Confederacy, seem so appropriate to Mordecai for the establishment of a Jewish refuge.

Noah was also a vocal opponent of emancipation, his arguments prioritizing the concerns of the white worker over any for the wellbeing of Black Americans. He wrote many essays and plays arguing against freedom for enslaved people. His anti-Black racism also manifested in his policy-making; in African American Theatre: An Historical and Critical Analysis, Samuel A. Hay notes Noah’s contribution to legislation that raised requirements Black people in New York had to meet in order to vote. Worse still, his prominence in theater allowed him to produce some of the first minstrel shows in the country giving him one of the main hands in fashion an aesthetic form of the de jure racism he already enacted.

The underlying motivations behind Ararat predate Zionism but resemble it undeniably. If Ashkenazi Zionism of the late 19th century was an answer to prevailing European ethnonationalism of the time, then I would argue Ararat was an answer to the colonial nationalism that brought about the American Revolution.

Noah’s story and the story of Ararat stands as useful context and parallel to the same American or — even more specifically — Upstate New York social climate that also produced the Latter-Day Saints movement. The United States was a very young construction, and those living within it looked to stories to cement their new identity. The Abrahamic idea of Promised Land, filtered and projected through the colonial apparatus of the United States, is a main driver of utopianism throughout the country’s history.

This is something I hope to juxtapose with its analog in Russia. I am beginning to believe that the religious authority possessed by the Tsar in the Russian Orthodox Church created different dynamics for religio-colonialism. While Protestantism was (and arguably still is) the implied religious norm of American society (Noah himself was removed from several diplomatic positions by Secretary of State James Monroe due to his Judaism), the foundational legal code of the country contradicts this, leading to more abstract notions of divinity on the American landscape and an indirect relationship between national identity and religious landscapes. I mean to say that the clay used to shape God in America was imbued with enlightenment liberalism. In Russia however, Russian identity and Orthodoxy were closely and explicitly intertwined. Communities were either Orthodox or they were not Russian; the land either was dotted with churches and cathedrals or it was foreign. In America, utopianists like Mormons and some Jews found roundabout ways to argue that they really were a part of a landscape which they had never visited, and that it was destined for them somehow. Mennonites, however, as a counterexample we will soon explore, as well as many Jewish migrants in the 1880s, seem to have been more practical in the relationships they held to their location, whether it be in Ukraine or Kansas — though they explored those relationships in different ways.

For interesting additional reading, I would recommend taking a look at the Mapping Ararat project, which was conducted through Insight Development Grant program offered by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and simulates the city based on the original plans with augmented reality.

I would also recommend Jacksonian Jew: The Two Worlds of Mordecai Noah by Jonathan Sarna for a more complete biography of Noah.

Thumbnail “Noah’s Ark” painted by Edward Hicks in 1846.

"the clay used to shape God in America was imbued with enlightenment liberalism. " It's funny how a a philosophical movement born out of a rejection of religious political authority gets absorbed by religious movements born out of rejection of political authority.